MOORE CORE DEUX: Delving into Comic Writing With Alan Moore, Part II

On the divisiveness of Moore, story structure, transitions, and pacing.

This is the second installment of my analysis of Alan Moore’s Writing for Comics, here is part I. you like what you read here and want more articles on the art of cartooning, subscribe!

On Alan Moore’s Writing for Comics (cont.)

On Chapter Two: Reaching the Reader; Structure, Pacing, Story-telling

Some might approach comic writing the same way a soft drink company approaches making a Coca-Cola rip-off, formulating an inoffensive concoction to appeal to as many taste-buds as possible. This is the authorial equivalent of creating a customer profile. Alan Moore makes it clear that he thinks this approach, writing for an imaginary average reader, is “arse-backwards.” In an effort to offend no one, Moore states, “There is a such thing as being offensively inoffensive.”

This part of the book is the most evident reminder of Moore’s divisive temperament: political, highly opinionated, and coming across as an insufferable, Rasputin-looking crank-lord in interviews. He’s been both critical of the comics industry and reactionary fandom. And I’ve come across a variety of strong political takes on Moore, from the view that his subversion of the superhero genre led to increasingly nihilistic comics, to accusations of his work being misogynistic and “problematic.”

But all of this just contributes to his point that you can never please all of the readers all of the time, so you just as well create something with integrity. But that’s not to say that Moore dismisses writing for an audience altogether, he just disregards calculating for public acceptability. He writes:

…When considering the person who will eventually be reading your comic story, the common denominator which you should be pursuing is not the lowest common denominator of public acceptability, but rather the denominator of basic humanity. If you’re reading this, there’s a fair chance that you’re a human being. There’s also a fair chance that no matter how unique and special you are or think you are, there are certain basic human mechanisms that you share with Conservative members of parliament, Yorkshire miners, radical lesbians and policemen.

Or radical conservative miner lesbian police. In short write for human beings. Also, write human beings. Moore’s criteria of writing through shared humanity naturally applies to writing characters. Though Moore later goes into the standard concerns about writing characters from diverse backgrounds (though he never says not to), I'll editorialize here and say that despite cultural differences we all share the lived experience of being human (libtarded but true!). In short, if you’re a human feel free to write stories about other humans (with an understanding that if you’re writing about radical conservative miner lesbian police some research might be in order, even if it’s just a porn comic. ESPECIALLY if it’s a porn comic!). Forget about thought cops, even inner ones. It sure beats the internecine combat over who-should-be-writing-who that plagued the Young Adult Fiction War of 2019. That kinda shit is exhausting!

Shape of the Story

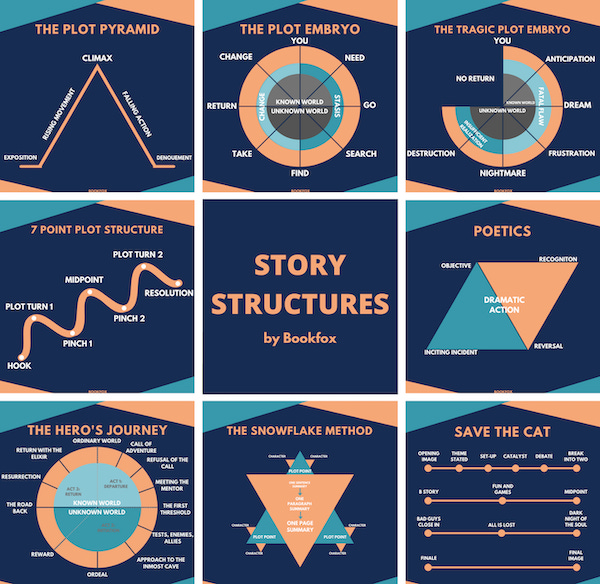

Stories are like women, they come in many shapes and sizes, and are all beautiful in their own way (most of ‘em). The myriad of story structures make pretty cool infographics (see below), and one challenge I’d like to meet is to make a double-helix-shaped story.

There are well-worn narrative models like three-act structure, and the Hero’s Journey, popularized by the myth-man himself, Joseph Campbell. This are all fine to study, but Moore isn’t formulaic, he doesn’t push specific story structures, he just emphasizes that you should understand the structure of the story that you’re writing.

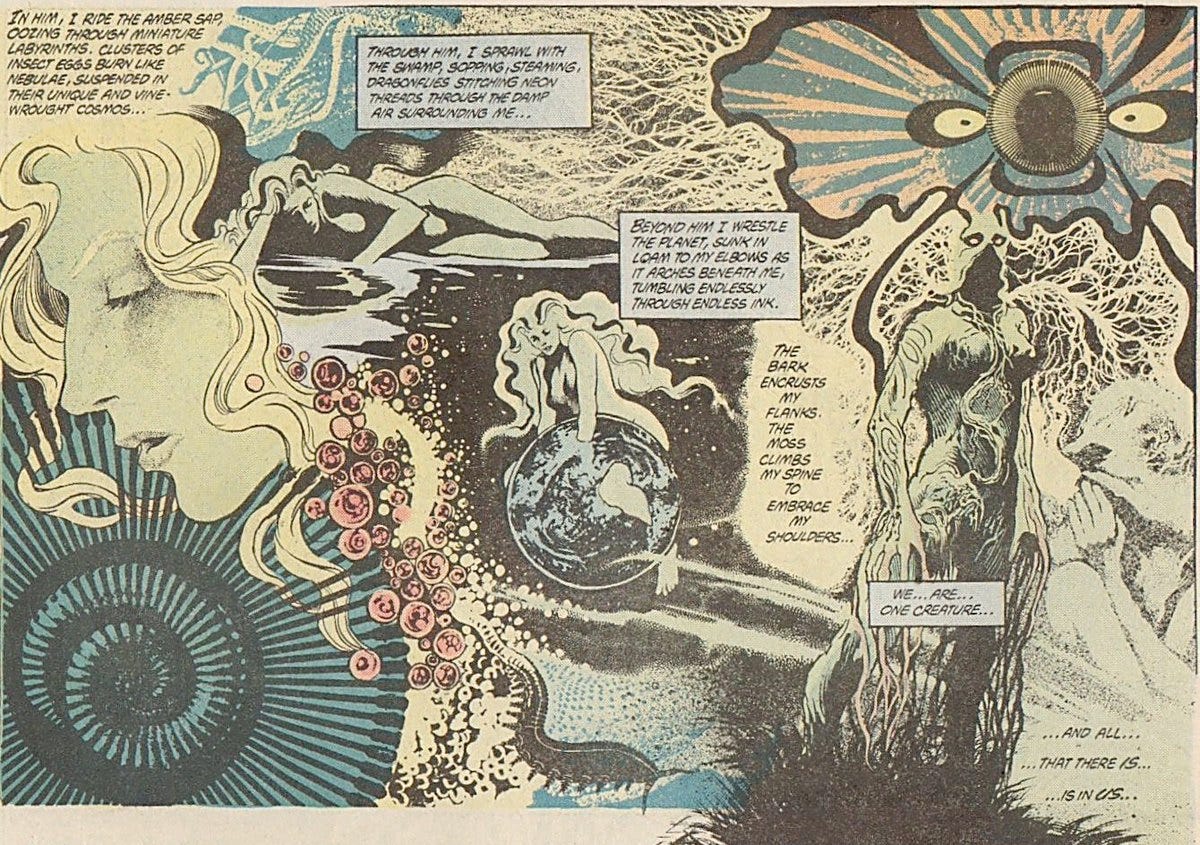

For his own work, Moore talks about a basic elliptical structure he often uses, where events at the beginning of the story mirror the events that happen at the end. These act as bookends to give a story a tidy sense of unity. He also uses a method where he starts out in the middle of the story and then fills in the background as the story progresses (he uses Swamp Thing #26 as an example). Moore’s open-ended approach to story structure appeals to the intuitives among us, artists who recoil from too much rigidity.

Some more unconventional ways of storytelling from the book:

He points to Swamp Thing #34, where the centerpiece of the issue was an eight-page erotic/abstract poem (now we’re cooking with fire!).

He admires his eventual collaborator Eddie Campbell’s informal, anecdotal storytelling.

He describes having a point A and B, with a non-linear and exploratory narrative between these two points.

There are other structures, including improvisational and stream of consciousnessness. Jim Woodring’s work comes to mind, which read like revelatory experiences. But even many seemingly improvisational stories often have some structure and planning behind them, and may function similarly as the last bullet point above (planned points with exploratory narrative in-between).

Transitions

Not beating his reputation for creepiness, Moore likens a good story to inducing a hypnotic sleep upon his readers. He elaborates:

Then, being careful not to wake them, you carry them away up the back alleys of your narrative and when they are hopelessly lost within the story, having surrendered themselves to it, you do them terrible violence with a softball bat and then lead them whimpering to the exit on the last page. Believe me, they’ll thank you for it.

… Okay … now that we’ve got that out of the way, Moore explains that transitions between scenes are the weak points in the spell that you are attempting to cast (oh, did I mention that he thinks of writing as magic?). Here are some transitory devices he mentions:

Overlapping or coincidental dialogue.

Synchronicity of image rather than words.

Coincidental linkage of vague, abstract ideas.

Use of color, Moore uses example of bloodshed transitioning to a scene of red blossoms.

Moore also uses an example of a dramatic transition in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds, when the heroine finds a bird-ravaged body and screams, but instead of showing us the scream Hitchcock abruptly cuts to a motor screeching up. While Moore admits that this wouldn’t work as well in the comic medium, even with the use of lettered sound effects, it could still inspire an imaginative mind to orchestrate such a device to words and pictures.

Pacing

Pacing should be invisible to the reader. Moore defines pacing as how long a reader will spend looking at a panel before moving to the next one. Regardless of the reader’s awareness, pacing is essential, whether you’re building up suspense or timing a gag. The most constructive criticism I received when showing some comic layouts to readers familiar with the mechanics of comics concerned my pacing (it sucked). So I paid close attention to this section of the book.

As Moore breaks it down:

A panel containing the standard 35 words of dialogue will take maybe seven or eight seconds to read.

A simple graphic image without any captions or dialogue will take maybe three seconds.

A fast action scene, maybe a fight scene, would likely work better if it moved as fast as possible.

On the last point, Moore uses Frank Miller as the prime example of well-executed fight scenes: silent-paneled, moving really fast, which flows like a real-life conflict. This contrasts with so many clunky fight scenes undercut with paragraph-laden dialogue (to the point of self-parody).

An example of clever pacing Moore points to is from Jaime Hernandez, in the Locas Tambien story 100 Rooms. The sequence involves an ex-nobleman kidnapping the main character Maggie the Mechanic. He removes the gag from her mouth, confident that she isn’t going to scream. He tells her, “Good girl,” and in the very next panel it’s obvious the two just had sex and the man is apologizing for his behavior (it’s soon explained that it was consensual). Hernandez’s adept storytelling in action.

While Moore can be experimental, I wouldn’t say his comic work is avant garde. Even Moore at his most experimental reminds me of William Faulkner, an author who played with form, but always in service to the story. In closing his chapter on storytelling, Moore emphasizes that approaches to storytelling are only limited by one’s imagination. The only requirement he suggests is that one should understand whatever techniques used. They should work best in conveying the story one wishes to tell, and anything that doesn’t serve that goal should be left out.

This is the second part of a three part series. Next up: World building, characterization, plot, and script! Subscribe to be notified!